Here’s a little-known fact about quantum computing: It sounds remarkably warm.

While much of the focus in quantum research has been on the race to build a useful quantum computer, one that far outstrips the computing power of traditional computers, a contingent from the Yale Quantum Institute (YQI) also has a second quantum endeavor in the works. They’re turning their data into an acoustic performance this Friday night, June 14.

“Quantum Sound,” part of the International Festival of Arts and Ideas, is set for two sold-out shows at 8 and 10 p.m. at Firehouse 12, on Crown Street. The 10 p.m. show will be broadcast live on WPKN radio. There’s also talk of putting out an entire album of quantum sounds.

“We purposely avoided the term ‘quantum music,’” said sound artist and composer Spencer Topel, who took on the challenge proposed by YQI manager Florian Carle to play superconducting instruments during a year-long artistic residency at the institute. Topel is a researcher and designer working with acoustics and sound, and his work has appeared in major venues and concert halls around the world, including Lincoln Center and Carnegie Hall.

“We’ll be introducing the audience to the quantum systems we use and talk about how they are precursors to quantum computers. These systems generate data that we then use to create sonic signals,” Topel said. “We follow this presentation with a 40-minute performance consisting of a controlled improvisation that we composed collaboratively over the last three months or so.”

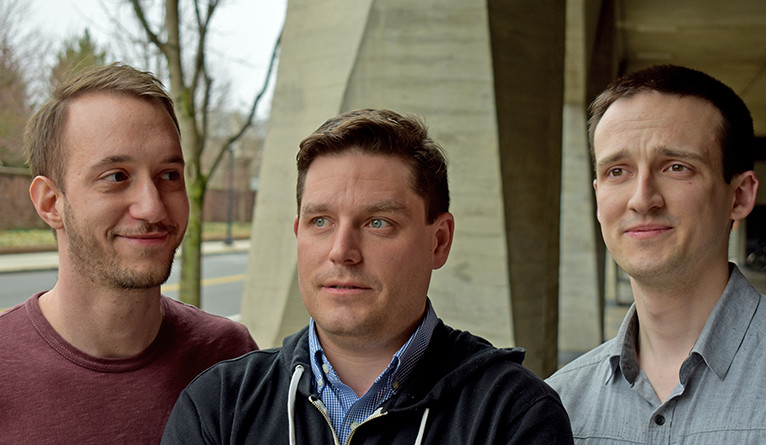

The “we” Topel mentioned are his bandmates — Yale physics graduate students Kyle Serniak and Luke Burkhart. Serniak, a long-time guitarist, came on board after hearing Topel give a presentation about his previous work; Burkhart, who has experience singing in musical theater, joined quickly thereafter.

For the Quantum Sound gig, this intrepid trio will perform the first-ever concert created from the measurements of internal operations of superconducting quantum devices. Their instruments — the superconducting quantum devices — are housed in special refrigerators that Yale researchers use to chill things down to near absolute zero for experiments.

Oh, and the fridges all have nicknames: Audiences may get to hear data coming live from JPC, Blue, or Lazarus.

The students’ experiments record electrical signals coming from the fridges, which Topel and his crew have spent months sampling — or as Topel says, “sonifying” them.

This is the crucial component of Quantum Sound, according to Carle, who will be giving the quick primer on quantum computing before the concerts. The team is adamant that the sounds being produced remain faithful to the characteristics of the actual data.

Topel said the concerts will open with sonification of the raw data with minimal processing. He, Burkhart, and Serniak will gradually slow down and mix the live signals to produce an artistic narrative that relates to the way quantum information is stored in qubits — electrical circuits printed on sapphire — deep inside the fridges during experiments.

The range of sounds includes moments of intense noise, intercut by melodies that are by turns diatonic, ominous, or almost imperceptible. Other moments sound reminiscent of winter landscape, populated by winds blowing through a mountain pass and looming storms. At times there’s a comforting flutter that brings warmth to the listener. Topel calls this a “wobble,” and it is created by the quantum “noise” that exists within the signal.

This all came together because what we’re doing with these sounds is so similar to what we do daily in the lab… That’s the only way it could ever work - Kyle Serniak

Understanding the interplay of elements within the fridges is what Quantum Sound, and quantum research, are all about, Serniak explained. “This all came together because what we’re doing with these sounds is so similar to what we do daily in the lab,” he said. “The parallels are there, so the sounds can be true to the physics. That’s the only way it could ever work.”

Burkhart had a similar reaction to the project. “When we heard the sounds corresponding to different qubit states, it clicked for me that the project was truly an interpretation of the science through sound,” he said.

Still, there is also a performance aspect of Quantum Sound.

At a recent rehearsal in a conference room at the Yale Quantum Institute, Topel, Carle, Serniak, and Burkhart gathered around a white table laden with laptop computers, sound boards, and a whole mess of wires.

“Can you guys send me some test tones?” Topel asked, as they settled into the rehearsal.

Soon they were jamming. Topel orchestrated as they each worked a board. Serniak bobbed his head; so did Burkhart. Topel worked his board with a flourish as if he were playing a Hammond organ.

They stopped after perhaps eight minutes and compared notes. “Hmm. That’s great. Let’s try it again,” Topel suggested. “Remember to punch it in. If there’s a section change, you just have to own it.”

Burkhardt offered an example. “Yes, that’s better,” Topel said. “Just so it has presence.”

They played on for another four hours, experimenting with pitch and determining which riffs make sense, making sure the data is not corrupted with audio artifacts that would have no physical significance in the signal.

“The idea here is seeing if we can use these systems as musical instruments, in order to get at new sounds and behaviors,” Topel said.

Come Friday, they might want to have an encore ready, as well.

Jim Shelton - Yale News